MS v. RS and BT: Not in children’s best interests to determine non-paternity claim

Described by the Children's Guardian as a "minefield”, MS v RS and BT (Paternity) is also an enormously sad case for the children involved.

The case concerned an application for a declaration of non-paternity by the ‘father’ (as he is described in the judgment) of two children, now aged 15 and 13.

I do not need to detail the history of the matter, even if it were known with any certainty - Mr Justice MacDonald, hearing the case, found both the mother and the putative father to be evasive witnesses. Suffice to say that the mother and the father were married in 2001, and the children were born in 2005 and 2006. In 2011 the mother asked the father for a divorce. Divorce proceedings were issued, and in 2013 a financial remedy order was made, pursuant to which the father currently pays £1,160 per month to the mother by way of child maintenance. The divorce was finalised in 2014.

The father claims that in about 2017 he began to have concerns that he was not the father of the children, and that the putative father, with whom the mother had worked during the marriage, and with whom the mother claimed to have commenced a relationship only after she had separated from the father, was the children’s father.

In December 2018 the father carried out a ‘surreptitious’ home DNA test, without the children’s knowledge. The test apparently indicated that he was not their father. The father issued his application in April 2019.

The mother’s position was that she doubted the integrity of the DNA test carried out by the father. She was prepared to undergo a forensic DNA test, but contended that the children should not be subject to further testing, and that the father’s application should be dismissed.

The putative father refused to submit voluntarily to DNA testing.

Otherwise, the evidence of the mother and putative father can perhaps best be described as ‘murky’. They both seemed to contend that the father was most likely the children’s father, but acknowledged the possibility that he may not be.

The most important matter was of course the position of the children. Their firm position was that they refused to undergo further DNA testing - they did not wish to know who their father was, and wanted to be left alone. In the circumstances, their Guardian submitted that it was not in their best interests for the father’s application to be determined.

Following the approach taken By Hedley J in Re D (Paternity] [2006] EWHC 3545 (Fam) [2007] 2 FLR 26, MacDonald J decided that whilst the court understood the pressure on the children and did not wish to force the question of testing, the issue of paternity could not remain unresolved forever. He said:

"I am satisfied that [the children's] fierce objection at this time to further testing is both deeply held and genuine. Against this, the children are each articulate and have engaged with the Children's Guardian. The Children's Guardian did not rule out the possibility that the children might ultimately change their mind in respect of testing if they knew that each of the adults had already provided samples. In this context, whilst satisfied it would be wrong to press the question of testing with an order taking effect immediately, I am satisfied that an order stayed without limit of time coupled with the children being told that the court understands and sympathises with their position, believes that it would be best to determine the question of paternity scientifically as soon as possible but that it will not force the children to do so, has the best chance of bringing a final resolution to this sad case. Equally, whilst satisfied that it would not be in the children's best interests to determine the father's application on the basis of the current deficient evidence before the court, the father's application should not be dismissed in circumstances where the court is leaving the door open to the provision of evidence of sufficient cogency to determine that application."

He concluded:

"To paraphrase Hedley J in Re D, there are sound reasons why it would not be in the children's best interests for this case to be determined now on the one hand and sound reasons why the question of paternity should now be determined on the other. In resolving the contradiction thereby created I am satisfied, for the reasons I have given, that the proper way forward in this case is to direct, pursuant to the Family Law Reform Act 1969 s 20 that the father, the mother and the putative father shall provide DNA samples for testing, the results of that testing to be delivered to Cafcass and held in a sealed envelope on the children's Cafcass file. In addition, I shall direct, that the children shall provide samples for DNA testing, but I will stay that order without limit of time and with liberty to restore to the court on not less than seven days notice to the parties. Finally, I will adjourn the father's application generally with liberty to restore.

"In addition to these orders, I will invite the Children's Guardian, when informing the children of the outcome of this hearing, to explain to them in age appropriate language that the judge understands their feelings of violation and confusion, that the judge therefore understands why they have said they do not want to participate in scientific testing and that the judge does not intend to ask them to do anything in this regard until they feel ready to do so. The Children's Guardian can also explain the view of the judge that the question of paternity, now it is out there, cannot be put off forever and that the judge considers that, ultimately, it would be better for the children to know the answer than not to know. Finally, in line with the evidence of the Children's Guardian, she can explain to the children that the adults will have provided their samples by order of the court before the children decide whether they are ready to do so."

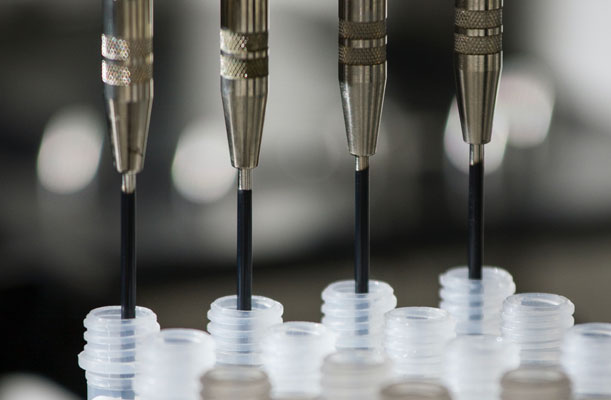

DNA samples photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Following the approach taken By Hedley J in Re D (Paternity] [2006] EWHC 3545 (Fam) [2007] 2 FLR 26, MacDonald J decided that whilst the court understood the pressure on the children and did not wish to force the question of testing, the issue of paternity could not remain unresolved forever. He said:

"I am satisfied that [the children's] fierce objection at this time to further testing is both deeply held and genuine. Against this, the children are each articulate and have engaged with the Children's Guardian. The Children's Guardian did not rule out the possibility that the children might ultimately change their mind in respect of testing if they knew that each of the adults had already provided samples. In this context, whilst satisfied it would be wrong to press the question of testing with an order taking effect immediately, I am satisfied that an order stayed without limit of time coupled with the children being told that the court understands and sympathises with their position, believes that it would be best to determine the question of paternity scientifically as soon as possible but that it will not force the children to do so, has the best chance of bringing a final resolution to this sad case. Equally, whilst satisfied that it would not be in the children's best interests to determine the father's application on the basis of the current deficient evidence before the court, the father's application should not be dismissed in circumstances where the court is leaving the door open to the provision of evidence of sufficient cogency to determine that application."

He concluded:

"To paraphrase Hedley J in Re D, there are sound reasons why it would not be in the children's best interests for this case to be determined now on the one hand and sound reasons why the question of paternity should now be determined on the other. In resolving the contradiction thereby created I am satisfied, for the reasons I have given, that the proper way forward in this case is to direct, pursuant to the Family Law Reform Act 1969 s 20 that the father, the mother and the putative father shall provide DNA samples for testing, the results of that testing to be delivered to Cafcass and held in a sealed envelope on the children's Cafcass file. In addition, I shall direct, that the children shall provide samples for DNA testing, but I will stay that order without limit of time and with liberty to restore to the court on not less than seven days notice to the parties. Finally, I will adjourn the father's application generally with liberty to restore.

"In addition to these orders, I will invite the Children's Guardian, when informing the children of the outcome of this hearing, to explain to them in age appropriate language that the judge understands their feelings of violation and confusion, that the judge therefore understands why they have said they do not want to participate in scientific testing and that the judge does not intend to ask them to do anything in this regard until they feel ready to do so. The Children's Guardian can also explain the view of the judge that the question of paternity, now it is out there, cannot be put off forever and that the judge considers that, ultimately, it would be better for the children to know the answer than not to know. Finally, in line with the evidence of the Children's Guardian, she can explain to the children that the adults will have provided their samples by order of the court before the children decide whether they are ready to do so."

* * *

DNA samples photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for taking the time to comment on this post. Constructive comments are always welcome, even if they do not coincide with my views! Please note, however, that comments will be removed or not published if I consider that:

* They are not relevant to the subject of this post; or

* They are (or are possibly) defamatory; or

* They breach court reporting rules; or

* They contain derogatory, abusive or threatening language; or

* They contain 'spam' advertisements (including links to any commercial websites).

Please also note that I am unable to give advice.